The season is over. The tuning forks are packed away, the music is back on the shelf, the black shirts have been tossed into the bottom drawer, and the last shreds of voices are being flogged through a dozen Messiahs before their tattered remains are embalmed in strong liquor. That’s all from our 10th-anniversary season, folks.

By our standards this has been a huge year. At around forty separate projects, the volume of activity has been almost double our previous busiest (2011), and at times it has felt overwhelming, not least as our behind-the-scenes team has consisted only of Juliet, myself, our agent Graham Hayter and our administrator Kathy Dallas. But there’s not a single project among them, not a concert, workshop or even rehearsal that wasn’t worthwhile, and among them there have been several of the best things I’ve ever been involved with.

Readers of this blog will already know some of the highlights: our Cage-athon in June that took in three concerts at Spitalfields and Aldeburgh Festivals in the UK; our Rihm Vigilia in Munich with musikFabrik; our Darmstadt debut in July; the premiere in Paris in November of Brian Ferneyhough’s Finis terrae; and of course the remarkable learning process leading up to the premiere of Aaron Cassidy’s A painter of figures in rooms.

But there have been many more: more Cage (in London, Cardiff and – most memorably – the Muziekgebouw in Amsterdam in November), more Rihm (Vigilia again, in Huddersfield)…more of everything. Perhaps most special of all was our official 10th-anniversary concert at the Wigmore Hall, where our Italian Madrigal Book project was launched with new pieces by Christian Wolff, Evan Johnson, Michael Finnissy and Larry Goves. The process of working towards that – and spending time in-depth with Gesualdo and Monteverdi besides – was one of the most intense rehearsal periods I’ve experienced (our gratitude, as so often, to Aldeburgh Music for a superb week-long Residency). And our final project of the year was not bad, either: Toujours et près de moi, a holographic madrigal opera (our first) engineered and directed by the talented Canadian director Patrick Eakin Young.

There was also time to give numerous student composition and vocal workshops and to make two new recordings: in February we finished our Rihm-Nono disc by recording the Sieben Passions-texte (watch this space for release), and in August we achieved a recording very close to my heart: new works, mostly written for EXAUDI, by Claudia Molitor, Aaron Cassidy, Stephen Chase, Joanna Bailie, James Weeks, Bryn Harrison and Richard Glover. It’ll be released on Huddersfield Contemporary Records in the new year. I’m so happy we’ve made this disc: this is a group of composers whose work we believe in passionately, and I’d begun to think we’d never get the chance to make proper recordings of these superb pieces. Heartfelt thanks to the University of Huddersfield and Aaron Cassidy for making it happen.

What’s next?

We’re taking 2013 as a fresh start. I’m looking beyond short-term plans and outlining some principles that will take us through our next decade. If the first ten years is about establishing, building a name and a reputation, the second ten should be about using them to achieve real artistic freedom. Above all, for us this means developing and deepening our relationships with composers of our own generation throughout the world whose work we believe in, and building new associations with the new generation. We’ve seldom had the opportunity to work with younger composers repeatedly – more and more I feel this is what is important to do, not merely moving in ever-widening circles for the sake of it (though to stop moving is to die, it’s true, we won’t do that).

Alongside that focusing is a determination to achieve bigger, more ambitious projects, and for them to take many and different forms. Much of the work we value doesn’t fit within the standard concert models, nor is our audience (such as it is) beholden to those models – so why bother with them? As for our audience, we need more of you – please spread the word to anyone who cares about new music.

There are some research questions I want to tackle, about vocal writing, about singing, about the art-form as genre. For instance, we need to open up a debate how voices can or might be used sympathetically in music that works at specific extremes – for example, temporal extremes or extreme reduction of material. I want to challenge EXAUDI’s singers still further, to experiment with new, unfamiliar and perhaps initially uncomfortable techniques and modes of expression, to work further beyond what they currently understand as ‘their’ way of singing. And I want to experiment with projects that reimagine the vocal ensemble or place it in new surroundings.

All this requires time and money, neither of which we traditionally possess, but there are some encouraging developments. We’ve had quite a good year for fundraising (arguably our first), and our inaugural full-time Ensemble Manager begins work on January 2nd, thanks to a grant from the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. We’ll be commissioning a bit more, too, so watch out for some very interesting premieres later in 2013. Among several long-term projects we have a particularly exciting one lined up for development throughout 2013, a multimedia installation by James Weeks and video artist Sam Belinfante.

Our more immediate diary, though not as chock-a-block as 2012, is still busy, with a tour of France and Switzerland (Gervasoni Dir-in-dir, with Ensemble L’Instant Donné) in January, new Italian madrigals in Antwerp in February, a Birtwistle rarity in Aldeburgh in March, a Ferneyhough reprise in Porto in May…and then in June Rihm’s Klangbeschreibung II and a new Posadas work with EIC in Paris followed by ten days at the IRCAM Academy.

There is an unbelievable amount more to do. The further we get the further we realise there is to go. It’s exciting to think we could still be doing this in twenty years’ time – and to have made a real mark on the face of 21st-century music.

*****************

This blog was set up to cover EXAUDI’s 2012 anniversary season. There’s been sufficient interest in it round the world to carry on, under a new title, in 2013. Thanks for reading and please continue to follow EXAUDI here, Juliet here and me here in the meantime.

We premiered Brian Ferneyhough’s latest work, Finis Terrae, with musikFabrik and Emilio Pomarico at the Festival d’Automne, Paris on 12th November. In advance of its broadcast on France Musique on 17th December, here are a few introductory thoughts about the piece:

Finis terrae – ‘The End of the Earth’ – has Ferneyhough now turned to eschatology? Is he finally releasing his apocalypse blockbuster?

No and yes; it may not outline a doomsday scenario in the Hollywood style (that might have been fun) but it does lay claim to a grandly post-human (or rather, human-less) vision of the world: its subject is moraines, the mounds and ridges of soil and rock debris, heaped up into ugly, barren landscapes by glacial movement. Here is the first part of Ferneyhough’s programme note:

‘After many years investigating the expressive potential of ‘damaged’ materials, in Finis Terrae I extend this guiding metaphor to consider the ravaged, rent and often grotesque moraine landscapes parsed by the vast forces typical of epochal glaciation. Although governed by an intractable geophysical ‘logic’, such formations cannot help but appear arbitrary and alien to the mind seeking to transcribe them into a dramatic framework based on human time-scales. As a result, we sense ourselves abandoned to a series of frozen catastrophic abruptions on an ill-lit terrain without obvious recourse to comforting fictions of organic perspective: we are strangers on the earth.’

An appropriate subject, we might add, for a world in the first stages of ecological disaster induced by man-made climate-change.

The piece is for eighteen players and six singers. Rather than being treated as soloists, the singers are trapped inside the ensemble, as Ferneyhough says ‘harried by its depredations and compressed into a claustrophobically narrow space only within which is a reductive form of survival possible.’ Musically this ‘reductive form of survival’ translates into an intermittent succession of short, tutti vocal passages (no individual moments of glory: this little group of humans has to stick together to survive) dispersed seemingly arbitrarily across the work’s time-frame, some stridently homorhythmic, others fractured and fragmented. There is a surprising amount of unison singing and speaking, too – another ‘reductive’ survival technique, an attempt both metaphorically and literally to assert their presence in this forbidding landscape.

(Indeed, Ferneyhough’s idea for the voices is that they be half-buried under the instrumental parts, never playing a concertante role but being immersed within the overall sound, sometimes but not always clearly audible. This ideal balance initially proved elusive; after some experiment the voices were significantly amplified and the singers placed, seated, at the front of the ensemble.)

What of the instrumental ‘moraines’ themselves? (Loath as one is to make so simplistic an identification, it seems impossible to avoid – and this almost baroque-style emblematising is hardly alien to Ferneyhough’s aesthetic universe.) They are intensely dramatic, with a gestural clarity that typifies his recent music. Pauses over barlines (with instruments holding their notes through) are used repeatedly to great rhetorical effect (‘frozen catastrophic abruptions’). A notably recurrent material-type at the start consists of string glissandi with scraped, unpitched guitar and percussion – quite a surprising Ferneyhough sound that seems to point, Xenakis-like, to the sounds of the extra-musical, natural world; we are reminded of this at the end, where the percussionists scrape across the skin of drums, a sound that seems to signal the impending closure of the piece, as it succumbs to a sclerosis of rigid homorhythmic pulsing across the ensemble.

musikFabrik were wonderful, as always – and we greatly enjoyed working with Emilio Pomarico for the second time this year, who had mastered the piece in no time at all. We performed it again on 24th November in Cologne, and the third performance will be with Remix Ensemble, conducted by Peter Rundel, on 18th May 2013.

Our other major premiere at Darmstadt was a Staubach Honoraria commission from German composer Niklas Seidl. Completely unknown in the UK, he works in Cologne as a composer, cellist and ensemble leader. His work is interdisciplinary, provocative and witty, and his piece for us, Animal Testing, saw five singers lined up at desks, each with a laptop, tape recorder or megaphone, frantically following commands fed to them through earpieces. It was quite disturbing, a bit mystifying and funny – all intentional. We hope to bring this piece to the UK in 2013.

I caught up with Niklas in September to ask him more about his work.

Your Staubach Honoraria commission for us this year, ‘Animal Testing’, was quite intriguing: can you describe the piece and the ideas behind it?

When Thomas Schäfer from the IMD asked me, if I could imagine to write for singers, I spontaneously said, I’d rather not to. Just because it is very difficult to write for singers and I think there are only a few good solutions from contemporary composers dealing with the classical beauty and sonority of a voice, that also has much more connotation to semantics and concreteness than instruments do. Especially for me, who is, at the moment, very interested in microtonal melodies and chords. I found it hard to project that on singers (who definitely can sing microtonal, but it always has the aura of a chromatic, in other words “round” sound) and would not want to try out special noises with the singers. All these reason gave me the reason to say: yes, I want to write a piece for singers, this will be a challenge. I know, that these kinds of challenges can be very childish and boring (as with composers who write for piano, only using the keys. that is more a kind of a sport for musicologists and “Tonsetzer”), but I had something in mind, that could work.

I decided to do samples of the singers and used them in a program, where they would produce their samples on a laptop-keyboard, playing these samples in different microtonal ways. this way, I had a prefixed instrument (like a piano) as well as the human aura (especially in the lowest and highest register, one could hear the characteristics of the individual singers very well.

Three of the five performers had these laptops, one used an old cassette-recorder to record himself and playback the material, the other one had a megaphone.

All of the singers had headphones, which would tell them via auditive commands, what to do. They either had to speak texts simultaneously, produce sounds from the sampler (specified by key) or do continuous hitting-movements with the finger or fist on several surfaces. They only had a score written on paper for the last 40 seconds of the 12-minute piece.

With this setup, the singers seemed like a medium, reproducing several kinds of secrets, that only they would hear on the headphones. Also in a classical sense a musician is a medium (either of a written score or his own feelings, for example in improvisations) and in this piece I exaggerated the idea of reproduction to different levels: the pre-produced medium of the sampled voice, the human being itself and the additional machines like cassette-player and megaphone.

Your pieces often seem to enjoy using short, disconnected sounds of quite different (and quite surprising) types, put together into unexpected juxtapositions. Can you say something about your main compositional interests and aesthetic?

I hope that I do have different ideas and interests in my pieces, but there definitely is a main importance, which can be characterised by unexpected juxtapositions. I am interested in musical history and material as well as in the troubles of daily life, which could lead to a music like John Cage made. but I am more interested in really composing these different ideas very precisely to discover the beauty of different levels of quality. As an image, one could imagine for example a nice candlelit dinner-table with exotic fruits on it, then some toothless people in sports dress sitting on the table, listening to jazz music, played on a toy piano and watching a horror movie on TV. But all these details (just to mention a few of such a nice image) are not randomly set, but a precisely chosen juxtaposition, thus also connection.

Pierre Bourdieu in his concepts of habitus and field states, that there are different types of capitals (social, financial and cultural capital) which overlap and change all the time, so that one cannot divide society into classes but rather into a field, where individuals can be on top and the bottom at the same time and their position changes all the time. I often try to use this concept as the theoretical basis for my compositions. nevertheless, in the end it is only a piece of music and these ideas do not have to be as concrete as in Animal Testing all the time.

If we search for your music online we come across a series of Hoerspiele on mySpace. Is that an important strand of your work?

I started doing Hoerspiele already at the age of 16 and it was my path into composition. I am still interested in the concreteness that radio plays can produce, but am more focused on instrumental composition at the moment. For the internet it is much more fitting to present electronically produced formats than recordings of live performances. That is why in the internet I have a different style than in the concert-hall.

Your piece talgwaren & Absterben. variations sur le nom Moritz-Willy, for three melodicas and slide projection, uses everyday advertising signage and the very ‘unbeautiful’ sounds of the melodica: what were the ideas behind this work?

I always wanted to do a piece with all the absurdities of daily life, that I love to take pictures of. The habitus of the melodica is very similar to these pictures: it is a common version of the much more refined accordion. in the 20s and especially in the 50s, people would meet to play folk music or hits from the radio in melodica-orchestras. The people did not need to practise much, the instrument is very easy to play and in a group, the harmonies work very well. but all these instruments were never tuned very well, so that although the instrument is fix in tuning, the intonation was quite microtonal.

I opened up the instruments and retuned them to some weird tuning (something close to quartertones) to exaggerate this idea of slight misuse (as the language on the adverstising signages is as well. There are always misprints and wrongly used “”-signs etc.)

What is EL ALFONSO ENTRETENIMIENTO?

Together with Paul Hübner I work on the ENTERTAINMENT-cycle since three years. We create works, starting with a name (in this case ALFONSO) and a concrete person behind it (King Alfonso of Spain) and start associating in every direction. These works are generally humorous but also criticizing certain cultural forms (in the case of ALFONSO the German tourists on the Spanish coast, and King Alfonso’s fondness for pornographic movies). we mainly use film and music as media, but also have installative objects sometimes.

The names are based on a piece by Hannes Seidl: the art of entertainment. And we started to play with the name.

Our works are so far:

The Adolf entertainment (about Austrians, Masses and a general Angst towards the unknown)

THE ARNOLD ENTERTAINMENT (about Arnold Schönberg)

EL ALFONSO ENTRETENIMIENTO (about King Alfonso and tourists in Spain)

THE PETER ENTERTAINMENT (about Pierre Boulez, Peter Eötvös, the Swiss Ziegenpeter etc.)

Coming up:

THE CLOTILDE ENTERTAINMENT (about Clotilde van Derp, expressionist dancing and the path from expressionism to fascism)

You’re active on the Cologne new music scene as a cellist and ensemble director as well as composer: what is going on in Cologne at the moment? How does it compare to the rest of Germany?

I am in Cologne for three years now and the scene is growing more and more after it was a little quiet in Cologne in the 90’s and 2000’s.

I think Cologne has a really good potential for contemporary culture because the heritage from the 50’s to 70’s (with the electronic music, Stockhausen, Siegried Palm, the Kontarsky-brothers, Caskel, later Kagel etc) left a lot of infrastructure that we can fill with new content and formations. Cologne was destroyed completely after the war and that gives a lot of possibilities, because there is no cultural heritage that we could sell to the tourists without moving on, as Italy is still doing. Also the boom of art in the 80’s with all the galleries, Martin Kippenberger etc, shows the potential of this, on first sight very ugly, city.

July saw EXAUDI’s first visit to the Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt. It was sad that we didn’t have more time to spend going to lectures and concerts and meeting the many interesting people gathered there: in fact, we arrived one day, did our concert the next day, a Reading Session the morning after and left at lunchtime. Too bad; next time…

Our concert seemed to go down quite well. We were asked to bring a ‘tasting menu’ of our ensemble’s core repertoire, so we took a cross-section of new British work: recent commissions from Ensemble Plus-Minus‘ Joanna Bailie and Matthew Shlomowitz, a new work from me for solo soprano (Juliet Fraser) called Nakedness and a new work from Bryn Harrison called eight voices. We surrounded that with pieces by Cage (Four2), Feldman (Only), Lucier (unamuno) and Clementi (Im Frieden dein, o Herre mein), plus a Staubach Honoraria commission from upcoming Cologne-based composer Niklas Seidl. I was quite conscious that we were not offering your typical Neue Musik (so many pitches, so much harmony) but it became clear that Darmstadt is not the party-line monoculture of old, and it was good to see serious new work exciting curiosity and interest for what it was, rather than opprobrium for what it wasn’t (which is not to say there wasn’t plenty of that flying around too). One is never stuck for opinions in Darmstadt – but how refreshing to be among people who really know their stuff and care about what they are hearing.

This post and the next one will offer more insights into two of the premieres we gave at that concert – the pieces by Bryn Harrison and Niklas Seidl. There will be a chance to head Bryn’s new piece soon when our HCR (Huddersfield Contemporary Records) disc is released later this year, and we intend to bring Niklas’ work to the UK in 2013. To kick off this two-parter, then, I asked Bryn some questions about his new work, and about some wider compositional issues.

You’ve not written for voices before. How did it feel to do this for the first time in Eight Voices?

I’ve written for solo voice before (most recently a piece called ‘Five Distances’ for voice and piano (2010)) but never for multiple voices. It was an interesting challenge. People kept telling me that they could imagine my music on voices and I was similarly interested in finding out how some of the weaving contrapuntal textures of my previous instrumental pieces might translate. So, in a way, I wasn’t approaching the piece that differently, but tried to keep the writing flexible enough to allow for changes in tessitura to be made where necessary. Some of the techniques explored (glissandi and moving from non- to wide vibrato for instance) are techniques that I have utilised in other instrumental pieces, particularly when writing for strings.

How does the piece fit into your current work overall – a new development or a continuation of previous preoccupations?

Most definitely a continuation of previous preoccupations. The harmonic language is conceived from chromatic pitch cycles that translated particularly well for voices I felt. Each set of two bars is essentially a self-contained harmonic unit which then repeats in the subsequent two bars. This allows for different repeated units to be juxtaposed on top of one another to create an ongoing tapestry of continual variation. The piece is presented in four sections or panels, each closely related to the last, which is something I like to explore.

Talking about the rehearsal process itself, did the piece sound as you intended? What were your concerns in rehearsal (concerns in the neutral rather than negative sense!)?

Yes, the piece generally sounded as I intended and the singing was truly beautiful. I try to avoid having too fixed an idea of the outcome, however. The changing numbers of repetitions in each part and the subsequent lack of vertical alignment in the score makes it extremely difficult to hear the exact outcome of every moment on the page. I was familiar enough with the harmonic language to know it would work, though. The tessitura issues mentioned earlier did present a small problem for the players as I hadn’t anticipated how difficult it would be to sing so quietly in those ranges, and odd phrases would stick out too much from the texture. These problems were easily rectified by taking the odd phrase down the octave.

Your work has always had a strongly integrated and consistent aesthetic – for me always seemed most closely related to the work of Feldman and Clementi in particular (Feldman most of all) – but that could be just my own perspective. Is that fair?

I think that is a very fair comment. I see my work very much as part of a tradition, coming, in part, out of Feldman’s late music – the pieces he wrote in the last decade of his life. I think one of the problems with contemporary music in general is that it is constantly trying to break with tradition, so there is no sense of continuity. Ideas are constantly fractured and dislocated. There is no opportunity for composers to build directly on the work of previous generations in an attempt to discover a personal identity of their own. I don’t see this as being a problem in other genres of music – jazz or popular music for instance. I studied Feldman’s music closely some years ago to the extent that I am only aware of all the differences now, rather than the similarities. I don’t really hear Feldman’s music in mine any more – my music is so much more linearly conceived than his, and the formal structuring very different. I acknowledge that there is still a close relationship there, though. Clementi’s music interests me a great deal and the notion of being able to look within a texture more and more closely is something I’m particularly fascinated by, although I have never made a detailed formal study of his music. I’m very keen on the music having an aesthetic, even surface quality to it, but this quality is something that has to arise from a synthesis of process rather than me sitting down to craft something beautiful that is simply sumptuous to the ear. The desire to work with a consistent musical langauge is a conscious one. I’m friends with several painters who see their work as almost being part of a series. There is no desire to do something radically different from one work to the next in the ways that composers sometimes do.

So what are your current compositional preoccupations?

Well, within this framework of a gradually evolving musical language, I’m trying to look at slightly newer ways to work with pitch cycles, including generating pitch material from juxtaposing different cycles together. I’m, also considering the use of microtones, which is something I experimented with somewhat unsuccessfully in a previous piece a few years ago. More generally, I’m very preoccupied with writing pieces that remain almost unchanged throughout – i.e. letting change occur in the listener’s mind rather than in the piece itself.

I was struck by your LSO orchestral piece, Shifting Light, which moves into tonal, almost ambient-music territory (you mentioned Brian Eno in the programme note). A one-off hommage, or will we be hearing more variegation of the overall harmonic spectrum in future?

One of the things that I particularly like about the pitch cycles is that they lend themselves to both a chromatic and a tonal/modal language. I wrote a piece for Asamisimasa (Linden quartet) several years ago that moves quicky from chromatic to modal material. I haven’t found a way of utilising that type of material in the pieces that I’ve written recently but I’m interested in perhaps allowing moments of tonality/modality to emerge. The ‘ambient’ reference was a nod to the past, really. I like to retain a degree of inner dynamism in the pieces, which I think is sometimes lacking from ambient music.

You’ve been teaching at Huddersfield University for some years now – that must be a stimulating place to work these days?

Huddersfield is a great place to work. Like any academic post these days the hours can be quite demanding, but I have some excellent work-colleagues, some good students, and a degree of autonomy in terms of my input into courses etc.

Listen to more Bryn Harrison here.

A short post to wrap up this series on EXAUDI’s Aaron Cassidy project.

The first and second performance of A painter of figures in rooms took place within half an hour of each other at the Purcell Room on London’s South Bank on 14th July, as part of the PRSF New Music 20×12 weekend. Nine hours of intensive sessions had preceded it, during which time we were able to take the piece on from the promising-but-inchoate state we had left it in Huddersfield in May, and turn it into a complete – even polished – performance. The energy and intensity of concentration in the room during those nine hours were something I won’t quickly forget.

Both performances went very well, though perhaps the second was slightly better – I, for one, was not quite relaxed first time round. We were delighted with the audience’s response, which was very warm, and after the second performance a good forty or so stayed around to pore through the score and chat to singers and composer. There was no sense of anti-climax, and it felt like a real event – thanks to the South Bank and the PRSF for that. (Thanks also to Owen Richards for these excellent photos.)

If you’ve not listened yet, the second performance was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 18th August and is online until the 25th August. Thereafter you will be able to hear it via download on the NMC website from 27th August until the end of the year. We have also just finished a studio recording of the piece which we’re very excited about, and that will be issued in the near future on Huddersfield Contemporary Records, along with pieces by Joanna Bailie, Bryn Harrison, Richard Glover, Claudia Molitor, James Weeks and Stephen Chase.

To have worked on this project has been a privilege: to undertake a genuine voyage of discovery, to push oneself as an artist and watch one’s colleagues doing the same, to have the time and space to work minutely and idealistically, and to come out at the end having made a significant work of art – these are not everyday experiences, however much they should be. Thanks to the whole EXAUDI team – Juliet, Amy, Lucy, Tom, Steve, Jon, Jon and Simon – to the PRSF, the South Bank and Huddersfield University who funded it, and of course to Aaron.

This blog will now move onto other pastures: a report of our recent activities in Darmstadt and at the John Cage Prom, and then on to our Autumn season, which is full of premieres and big events. Please keep reading!

In advance of next Saturday’s premiere, Aaron Cassidy writes:

One of the great challenges of presenting and discussing my work over the last several years has been pulling the conversation back from technical, practical, logistical issues and regaining a focus on aesthetic, artistic, musical ones. I am aware, of course, that it is in many ways the notation – and the unusual performance techniques and approaches to instruments/voices that made the development of that notation necessary – that gives the works their identity, or at least, on the surface, gives them their uniqueness. But it’s also clear to me that this focus on the practical, factual aspects of the work is far too easy (it reminds me in many ways of the analyses of early 20th century repertoire that I had to do as an undergraduate in which we were identifying pitch sets or serial row transformations without ever actually engaging with sound in any real way, much less wider cultural or social contexts), and it risks turning the notation and the performance techniques into a kind of gimmick, a shtick, or, as I am increasingly discovering, a ‘brand’.

I’ve been concerned in the lead-up to next week’s premiere at how easy it is (in marketing materials, brochures, etc.) to make this piece sound like a bit of a Science Fair project. The descriptions often deal with the nuts and bolts, the exploratory tinkering, but it’s been quite difficult to steer that conversation back towards the things that were actually important to me in the construction of the piece. It mistakes the means for the end. In an effort to fight back, as it were, I thought I’d take the opportunity to talk here a bit about the title of the work, which I hope might help to put the piece into a larger expressive, artistic context.

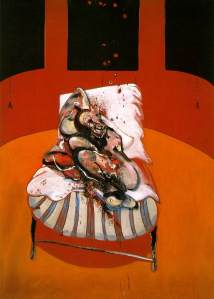

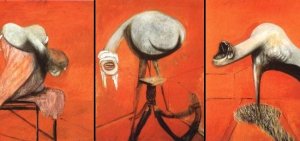

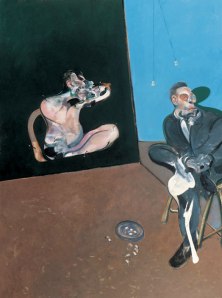

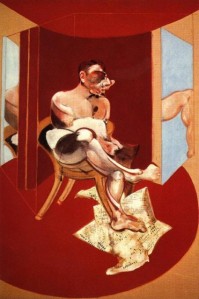

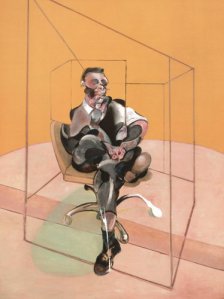

I have a longstanding interest (for a time, it was nearly an obsession) with the paintings of Francis Bacon. An earlier collection of works (solos for trumpet and trombone, an oboe/clarinet duo, and a work for small ensemble) was based on Bacon’s 1944 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, alongside Gilles Deleuze’s fantastic text on Bacon, The Logic of Sensation (which provides the titles for the works, as well as all of the texts that comprise the accompanying programme notes).

In that case, what I was most interested in was the twisted musculature, the wiping, the smearing, the distortion and dislocation of bodies and limbs and faces. I’m fascinated by the fact that the images in the triptych are otherworldly, anthropomorphic, yet are still somehow immediately, identifiably, fundamentally human. Indeed, the separation and dislocation, in a sense, reveal that humanity.

In the case of A painter of figures in rooms (a quotation from John Russell I found on an exhibit label next to Bacon’s Painting 1950 in the Leeds Art Gallery), I was focused on Bacon’s many portraits and in particular their treatment of mouths and faces. It’s difficult for me to describe my emotional reaction to these faces, but that is, I suppose, exactly what attracts me to them. There is a raw expressivity to these distorted, smeared images, somehow a direct connection between these horrifyingly mangled faces and a kind of unfiltered, unnameable human emotion. It seems, as well, that it’s almost always the mouth that is the most twisted and distended – it’s always clearly a mouth, and it’s often a mouth that is identifiably snarled or screaming or shrieking, but it’s in the wrong place, its proportions are wrong, it’s deformed and frightening. It is the most ‘outward’, immediate aspect of a body that is similarly dislocated, seemingly twisted in on itself in a tangle of limbs and organs.

There is another important aspect to the paintings: there is, in each case, a sense of bounding, of containing, of constricting. Bacon’s ‘rooms’ play a crucial role, their simple geometric forms enclosing the figures in an unreal space, in a space whose geometries seem to maintain multiple perspectival layers which all seem to push against the figure in multiple directions. It’s a fascinating phenomenon – the background in these paintings is often exceedingly simple, but it isn’t flat, it isn’t static. Its simple circles and lines, its angles, its improbable mirrored reflections of the figure all push back against the space, not so much defining the space as scrambling it. There are many similar forces at work in this new piece. All of the various physiological states that have been discussed in the earlier blog posts – movements of the mouth, tongue, larynx, lungs, etc. – do not happen in an unconstructed, boundless space. Rather, at any given moment, the available space of those movements is in flux, the precompositional sketches prescribing for every physiological layer both a range of available movements and a space in which those movements can take place. What is important here (and, this for me is an essential connection to the Bacon images) is that the unusual recombinations of mouth shapes and tongue position and larynx tension and breath flow are a result of an underlying friction, a series of streams of resistance, pushing and pulling and wiping and smearing and obliterating.

The fact that this happens with the mouth, and more importantly with the voice, is crucial. What results in the Bacon, and what I’ve set out to achieve in A painter of figures in rooms, is a kind of unfiltered expressivity. I’ve aimed to generate a direct and immediate form of vocalization that isn’t filtered through speech, through language, through the usual self-aware, reflexive ways that we tend to use our voices. What this requires, for me, is a dedicated avoidance of an approach to the voice that ‘sounds like …’. It doesn’t refer to anything outside of itself. It is the physiology of the voice laid bare, but, like the Bacon paintings, there is no way to dislocate the mouth, the voice, from the self.

25th June

I’m sitting on the train feeling very tired and completely inspired. EXAUDI has been paying homage to John Cage this week, which means four completely different concerts in four days: two at Spitalfields and two at Aldeburgh. I think we covered most of his work for multiple voices – not many more pieces I can think of!

On Tuesday, Jon Bungard and Mandy Morrison, with animateur Sam Glazer, led children from two Tower Hamlets primary schools in a Cage-inspired performance in Spitalfields.

On Thursday, we performed a late-night concert, again at Spitalfields, in which we sang Four2, The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs and A Flower (both of these with Amy Moore), Four Solos and Hymns and Variations. Great music all: Four Solos doesn’t get done much now that Electric Phoenix are no more, but it’s a total romp, and our quartet of Mandy, Lucy Goddard, Jon Bungard and Jimmy Holliday gave it everything. For me, Hymns and Variations is a desert-island piece, one for the ages. I love everything about it, the felicity of the connection Cage makes with the past (Billings hymns), the transparent technique (random erasing of notes and equally random extending of those that are left), the perfect matching of technique to aim, the subtle yet overwhelmingly beautiful shifts of tonality between plain old C major and plain old F major, the endlessly nuanced dynamics roughing the surface just enough: the sheer exquisiteness of sensibility in every part of the composition. The man was a genius.

It’s a bugger to sing, being nearly half an hour of senza-vib isolated notes with infinitesimal dynamic gradations, all in the simplest tonality where a few Herz either way can seriously derail the tuning, and (being amplified) every tiny scuff or blip of sound is magnified. Just as well that the occasional bit of dirt makes it all the more human and all the more poignant, as it would otherwise be a heart-breaking labour of constant imperfection. As it is, once you’ve rehearsed it to a certain level – the tuning fixed, the dynamic levels set and secure, the vowels learnt, the overall sound and sensibility understood by everyone and the way single sounds connect physically to each other (because you have to, even if they are all conceptually monads, and there is no ‘logical’ connection to them) homogenised across the ensemble – once this is done, there is nothing left to do but sing the piece, and hope for the best. We were fortunate in St Leonard’s Church to have a helpful acoustic that just gives everyone a bit of confidence – and I think it went well! I sincerely hope we get more chances to do Hymns and Variations, as more people need to hear this masterpiece than the paltry (but enthusiastic) crowd that turned up on Thursday…

So then, on to Saturday, and Aldeburgh, where we mounted two performances of Cage on the same day. The first was our Musicircus, into which was inserted our new, improved and expanded version of Song Books – the Cage piece that just keeps on giving (we’ve still not done all 90 of them, not by a long chalk). This was an unalloyed joy. I admit I was worried (being the Curator of the overall event) that the plan of meshing these two pieces, and of doing a Musicircus in a series of interconnected spaces rather than one big top, might be both inauthentic from a Cageian point of view and not very effective. Hell, I wasn’t even sure if Musicircus works as an event at all. From my perspective these fears turned out to be unfounded, as it was really a wonderful show. The four electronics setups for Song Books (the excellent team from UEA – Seb Fosdal, John Kramarchuk, Jon Gatiss and Greg Hobson, along with sound artist Bill Thompson) were dispersed through the spaces, and around them we had a Peruvian band, a several folk acts, a country-western duo, string quartets and duos, a koto, Jordi Savall, Pierre-Laurent Aimard (in Fluxus mood), Tamara Stefanovich, film with live electronics, Zoe Martlew (a one-woman Musicircus), Colin Matthews playing Vexations, and of course all sorts of EXAUDI goings-on from the Song Books (the singers were Juliet, Amy, Tom, Jon Bungard and Jon Saunders). There were also drinks, cake, bunting, balloons and even sunshine. It was exactly what I like to think Cage wanted – an anarchic harmony, fun and wonderment round every corner. I don’t feel I can take much credit for it coming off – it was made by the performers and the audience, all of whom got immediately into the spirit intended – but I can say that I’m very very glad it did!

If that wasn’t exhausting enough (it was, more than), we’d also agreed to do a Pumphouse gig in the evening. The Pumphouse is a really nice venue, a very intimate building on the outskirts of Aldeburgh, and seems to be where some of the most interesting things in the whole festival take place. We brought three singers, Bill Thompson, the artist Sam Belinfante and me. The programme had tribute pieces from Bill, Sam and me, and Cage’s Living Room Music, Variations IV, Ear for EAR, The Wonderful Widow and A Flower again (this time with Juliet), a fragment of Indeterminacy and Radio Music. It seemed to go down well, Sam and Bill’s work was lovely, and I enjoyed myself as much as I’ve done in any concert for a long time. There will be more Cage shenanigans this year for us, but I doubt they will top the memory of these past few days. It’s been really glorious.

Thank-you, John!

Lest this blog begin to seem obsessive, I’m taking a few posts to catch up with some of our other projects this summer. June is always one of our busiest times of year, being the summer festival season, and this year has been no exception, with visits to old stamping grounds in Aldeburgh and Spitalfields and our first trip to Musica Viva in Munich on 15th.

Taking Rihm to Germany feels a bit coals-to-Newcastle, so I suppose it was quite an honour to be asked to provide the six singers for Rihm’s Vigilia, a monumental (of course) meditation on Passion Week texts, accompanied by the superexcellent musikFabrik and conducted by Emilio Pomarico (to whom I was more than happy to cede conducting duties and enjoy watching a master at work).

The premise of the piece, what it’s doing and how it does it, is, as Emilio remarked, quite familiar, indeed Romantic – but as always with Rihm he stirs things up so that it’s never quite straightforward. Pure harmonies are dirtied, compromised; lines are broken or stop short unexpectedly, like tricks of false perspective; ideas seem to build then fragment and disjoint, sonorities are muddied and dispersed through extended techniques. Conventional expressivity is seen through a cracked mirror. The seven a cappella movements, separately known as Sieben Passions-texte – are interspersed with instrumental Sonatas, followed by a Miserere for singers and instruments. The instruments are low-string and low-brass trios and percussion onstage, clarinet and horn ‘im Raum’, and organ wherever in the building that is. So it’s a ritual structure with strong echoes of Venetian spatialised church music (a little connection with Rihm’s sometime hero Luigi Nono there, too?).

We’ve done the a cappella movements of Vigilia before several times, and even recorded them (Producer: A Cassidy – just to keep him in every post). Apparently Rihm was listening to Gesualdo a lot when writing them – a fact enthusiastically relayed to me several times over the course of our trip, as if to justify their peculiarities – but as a Gesualdo fanatic I don’t find its influence on Vigilia particularly interesting. Yes, you can see Rihm ‘consuming’ Gesualdo here: the a cappella movements are kind of tonal but with crunchy chords and swerves of tonality, and a constant sense of chromatic dislocation and general tonal apostasy (I actually find this music genuinely transgressive, which is not easy to achieve nowadays. That’s what I like most about it). But really, Gesualdo doesn’t disturb the Rihm equilibrium that much, so it feels less a meeting of minds and more a kind of flavouring (probably the idea), which occasionally comes to the fore but not very often. If anything, I think more of Bruckner than Gesualdo when listening to them.

None of which is to say it’s not a good piece: we love it. It’s a huge sing, its big, muscular shapes stretching the voice and its unbridled (frequently outrageous) tonal (or off-tonal) harmonies and progressions sounding glorious across the ensemble. Some parts (first tenor especially) are shockingly high and loud for long periods, and we’ve just about worked out a way of pacing ourselves so we can really go for them without getting exhausted half way through. Steve, our first tenor, says he’s grown into the ‘role’ since we started singing it – certainly five years of maturing voices have helped make this piece more comfortable for everyone – without, I hope, destroying the sense of fragility and risk that makes for a great performance.

From where I was sitting in the Michaelskirke (Lassus’ church) it really was pretty fine. musikFabrik is such a great ensemble – precise, dramatic, a huge range of colours and dynamics and technically so solid. Their instrumental Sonatas came across as finely nuanced and expressive in spite of the bathy acoustic, which threatened to swallow everything at all points but somehow never quite did. Three cheers to the organist, Francesco Filidei, for keeping up in spite of being about 300 yards away from the action. Nor would I have relished having to use three separate intercoms to keep in touch with organist, clarinettist and horn-player during rehearsals – I’ve no idea how Emilio kept his patience, especially as from where he was standing all three players were virtually inaudible!

However frustrating the acoustics were, the venue made for a quite special performance. There was a sense of space, of the numinous and transcendent. We were drawn inwards to moments of intimate pathos and then flung outwards round the church in echoing cries. Doubts I’d had about sections of the work evaporated, as they so often do with Rihm in the actual performance – the man knows the drama of the moment as well as anybody. And what a nice surprise, too, to meet him afterwards.

EXAUDI is, more often than not, a conducted ensemble; but it’s also a rather small ensemble and makes what one might call chamber music, and in many of the pieces we do it’s either preferable not to have a conductor or absolutely essential not to have one. Although I always take a directorial role in the preparation of performances, and take responsibility for the all but the most personal interpretative decisions that are made, what I actually do and how I do it is extremely flexible according to the demands of each piece, from fully conducting to something more akin to coaching or artistically advising. Working with the same people over a long period of time means of course that roles have evolved as we’ve got to know each other better, learnt to trust each other with particular responsibilities (or not), and found ourselves wanting to develop and extend our working practice both individually and collectively. Right from the start I’ve had the belief that, especially in challenging and strange new music, each musician has to feel personally invested and involved in the collective process of getting to grips with the work: thus I’ve always tried to present my role in a small group like EXAUDI as that of primus inter pares, where each musician can have their say and their opinions carefully considered, rather than project a rigidly hierarchical framework.

That said, this only works because we are, broadly speaking, comfortable with our roles and respectful of each other’s (overlapping) fields of expertise. One can take flexibility too far, and many a small group has come to grief through getting roles confused or through tensions being created through people’s ambitions being inappropriate to their talents in a particular area. I sometimes wonder if this isn’t the inevitable entropy of every human grouping with even the slightest pretensions to democratic organisation: after all, a group in which roles are completely demarcated, even by consent, is almost certainly one where full creative potential is being stifled, so the line between sticking to roles and moving outside them is one that has to be constantly monitored and sometimes redrawn if one is to maintain the best possible working practice and the highest standards.

In the case of Aaron’s piece, the roles are, at least on the surface, hyper-defined: each singer is in sole charge of his/her part (and little else, not least as s/he only has his/her part), and the conductor is…well, he is certainly in control of the beat…but what else besides?

My usual practice when learning a new score, whether Cage or Ferneyhough, is fairly early on in the learning process to put myself into the shoes of each musician and learn all of their individual parts. My aim is to be able to view the work from everyone’s individual perspective, to know all the difficulties, to see the work from the view of its individual lines, and of course to know it well enough to be able to correct any and every mistake that is made (though it’s not always appropriate to do so). To me, this is best-practice score-learning, and I am not comfortable completing the ‘vertical’ learning of the work unless I’ve done all of its horizontal lines at some stage first. Whether or not this is a personal foible (I’d love to know how others go about it) – certainly my natural inclination is to see things contrapuntally wherever I can – it’s not always possible or necessary to do it in the amount of detail in which I learnt Missa Brevis, or Dillon’s Hyades, or Lachenmann’s Consolation II, or (a real neighbour-basher this) Xenakis’ Nuits.

Aaron’s piece, however, is the only purely-vocal piece I’ve conducted where this is, realistically, impossible. Not only is each part of a complexity to keep each singer busy for several months, but the indeterminacies are such that every phrase will come out at least somewhat differently with each person that executes it: even if, in an ideal world, one had several years to learn the score in this way, the sounding results could be at times almost unrecognisably different. The problem is encapsulated by an example from the April rehearsals: I picked a singer up on their vowel sound, transitioning as it was between mouth shapes and tongue positions. More ‘er’, please, not so ‘ah’. ‘But my tongue is in the right place and so’s my mouth shape.’ We compared: it transpired that there was a subtle but definite range of ‘correct’ vowel results for the parameters prescribed at the point I’d marked, and that if anything, his was closer to the centre of that range than mine. In the end, how you are personally conceiving of the precise location of each tongue position, or a mouth shape, or even (dare I say it) of the resulting sound, still makes a difference to the final result; take, for example a variable such as the rate at which transitions are made and the exact point where an ‘o’ mouth seems to become more of an ‘oo’. Sure, it’s theoretically possible to correct a singer – in a one-to-one scenario, for example – on pretty much any of the notated parameters; but in so many cases the actual sound that comes out has a small but significant range of ‘correct’ readings. So not only are you ‘learning’ the part, but also learning the infinitesimal variables that will make the part different in someone else’s mouth. Not easy!

In short, I went as far as I could. I broke the piece into thirty sections, and, section by section, first of all learnt the beating patterns, the tempi and some of the clearest gestural outlines of the music – points of climax, of rest, and so on. Next, I looked for clear topographical features such as rhythmic unison passages (there are lots) and big solo moments, and then built up the rest of the texture around them, section by section. In doing so I ‘sang’ through every part in a kind of busking way, taking into account that there are some techniques that the singers are spending months to master and that there was no hope of my doing so. I wrote in a crib sheet of likely resultant sounds under each note – something that a number of the singers are also doing in order to get a handle on a phrase, though this is contrary to the spirit of the decoupling ideal. But it does help to get the first grip on the material, and for me as for the singers the challenge now is to move away from such aids and see the music as a play of physical interactions rather than of resultant sounds. Finally, as I went through I noted what I thought would be special points of detail using tiny squares of fluorescent post-it notes – many of which turned out to be far less important that they looked on the page when put into context!

All this took the best part of a month, and in the three days remaining before the Residency I went through the whole score again, ensuring that as far as possible I recognised each section and its key moments (ridiculous as that seems, when there’s no fixed sound in your head and the score is consistently and densely detailed, you can’t assume even this!) and was ready to tackle each section in rehearsal in a coherent way by noting (post-its again) the main textural strands of each section.

Had I learnt the score? Emphatically not. But if I had finished, and was completely ready to perform it by that point, I doubt I could have got in amongst the detail in the way that was necessary in those Residency sessions. It’s often the case in these all-too-rare ‘long-haul’ rehearsal periods that if you are too far ahead of the performers you aren’t in the best position to help them. The fact that I was still bound up in the details with them meant we interrogated the questions in a very thorough and patient way – although I struggled with the fact that to really judge the success of each performer’s efforts you have to be simultaneously watching the score and their mouth – so it was good to have the composer sitting behind me to spot what I didn’t.

Even so, I felt uncomfortable. Uncomfortable that I didn’t have the clarity of overall vision of the score that I wanted, though this will eventually come; uncomfortable that the nature of the material means that I will forever fall short of that final sense of physical mastery that each singer will eventually have; uncomfortable that I have the feeling that I may never be able to conceive of even a single bar in all its proliferating, abundant detail. When I’m conducting, I want to possess every tiny part of a work, whatever it is – to encompass it, to feel as I conduct it that it is somehow embodied deeply and wholly inside me: in this piece I’m not sure I ever will. There is a kind of melancholy to that realisation that cuts through the exhilaration I know I will feel when we perform it in July – it will always be beyond me, slightly.

For now, the challenge is at least to get to know it all better: details, larger shapes, everything. I’ve planned four passes through the whole piece between now and July, moving from outlines to fine details and then attempting a holistic integration. My job, as well as beating time, giving a few leads, and shaping as best I can the larger forms and paragraphs of the work (though I’m not yet certain how to achieve this beyond making the singers aware of them – how much, really, can they make larger shapes once they’ve executed their lines as correctly as possible?) is to help the singers get closer to individual mastery of their part, moving between the fine details and the larger gestural shapes, and then adding that altogether to create something that makes musical (yes!) sense of the tangle of individual lines. I have a sense of the clarity that we are searching for and it is that I have to find and bring out – and to do that I have to keep moving more and more deeply into the piece. I need to prise out the larger intentions in every bar as well as the details, and find a way to draw them out of the singers. (Just explaining their role in the texture (yours is a solo line, you two have a duet here) will be a good place to start – so that everyone becomes aware of what is going on around, and their place within it…)

Much ink has been spilled over the role of notation in hyper-complex music, and I wholeheartedly concur with those who would argue that the job of the performer in these circumstances cannot be simply to present a perfect rendition of everything on the page: the point is that perfection remains slightly out of our reach, and we have to choose a path through an informationally-overloaded notation that brings us as close as we can get to as much of it as we can encompass. For Cassidy as for Ferneyhough, hyper-complex notation is, I think, intended to achieve what the latter calls ‘a dialogue with the composition of which it is a token, such that the realm of non-equivalence between the two…be sounded out, articulating the inchoate, outlining the way from the conceptual to the experiential and back.’* If that is so, then our role too as performers might also best be framed as a dialogue between ourselves and the work, mediated by its notation, and that that dialogue by its ungraspable nature be both ever-changing and unending.

The key is to continue the work, strive for ever new insights and mastery, but to give up naive ideas of achieving perfection – which after all have never done anyone any good. It’s Beckett’s famous old quote – ‘Fail again. Fail better.’ – melancholy for sure, but beautiful, and in the end true-to-life.

* I am indebted to Stuart Paul Duncan’s article ‘Re-Complexifying the Function(s) of Notation in the Music of Brian Ferneyhough and the ‘New Complexity”. Perspectives of New Music 48, no. 1 (Winter): 136–72, for a useful overview of the topic.

We’ve asked the singers if they’d like to contribute a slightly longer description of the learning process for Aaron’s piece. For regular readers of this blog there might be a risk of overkill here, but what I hope might become interesting – and of course applicable to the learning of all sorts of different pieces, not just this one or pieces like it – is how very differently people approach an overwhelmingly complex task. I hope to twist a few more arms into submitting their Learning Processes to public scrutiny, and I’ll do the same myself – but for now, here’s Simon Whiteley’s take on Challenge Cassidy:

The mere fact that there are three pages of performance notes for A Painter of Figures in Rooms tells you that it’s not your average piece of music, and certainly not when it comes to learning it.

It is a completely graphical score, the only really recognisable musical parts being the time signatures and the rhythms. This was my initial starting point: start with what you know! Unfortunately, the rhythms aren’t too simple either: every bar has a radically different time signature to the last, and most bars have some fairly tricky tuplets in them.

Having spoken to Aaron about the piece, it is clear that it is incredibly meticulously and exactly laid out and composed. As such, I wanted my rhythmic accuracy to be as great as possible. I therefore turned to Sibelius (music programme, not composer) for some help. My learning process consisted of about an hour a day, or one ‘gesture’ per day, for roughly 6 weeks. The first part of it was to put each gesture’s rhythm into the programme (on an A, usually staccato) and then listen back with the metronome clicking until I got the hang of it. Easy part done.

As people are most likely aware by now, the piece takes the voice to bits and puts it back together in its composite parts: fold tension (‘pitch’), air pressure (‘volume’), mouth shape, glottis position/tension and tongue position. Every ‘note’ has each of these stipulated. Many vocal effects and extended techniques are employed as well: tremolos, trills, in-breathing, pitched and unpitched consonants, to name but a few.

So, where to begin? Combining the mouth shapes and tongue positions gives a good overall sense of the sound required. For example, if you are using an ‘oo’ mouth shape with an ‘ee’ tongue position, the resulting sound is a closed ‘ü’. Therefore (only as a starting point – don’t worry, Aaron) under each ‘note’ I wrote the overriding sound. It was then a case of learning to perform these with the rhythm, and then adding different layers of specificity. For example, my first gesture starts with some very quickly moving mouth shapes and tongue positions, so it took a while to work out the overriding sounds. I then had to think about the tessitura (very high but always changing), then added the trillo marks and the dynamics (very quiet). I’m sure this all sounds very complex, but luckily it was all in black, meaning a ‘normal’ glottis tension: perhaps the only ‘normal’ thing about my first gesture!

Once I’d repeated these steps with the first few gestures, it became a lot more innate, and the whole process a lot easier. This breaking down of the different features and then building up of layers was painstaking but necessary. At least, it was the only way I could think to do it.